Research

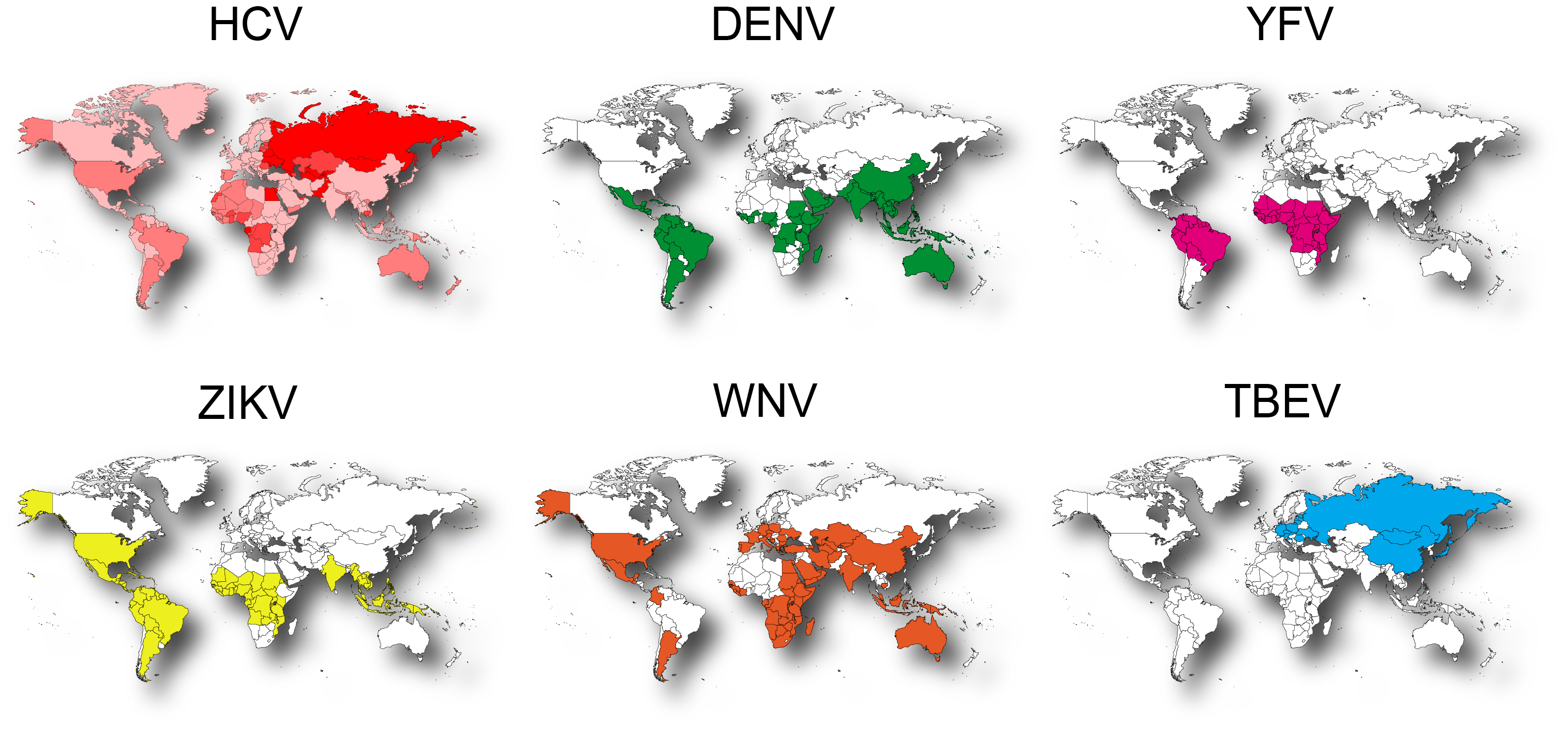

The Herker lab studies the cell biological and metabolic consequences of virus infection with a focus on lipid metabolic processes and host cell lipid droplets (LDs). Our focus is on positive-sense RNA viruses of the human pathogenic Flaviviridae family. In addition to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, which affects over 70 million people and causes over 400,000 deaths annually, the flaviviruses transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks such as dengue (DENV), yellow fever (YFV), Zika (ZIKV), West Nile (WNV), and tick-born encephalitis virus (TBEV) cause severe acute infections that contribute significantly to the disease burden, especially in developing countries.

Global distribution of flaviviruses.

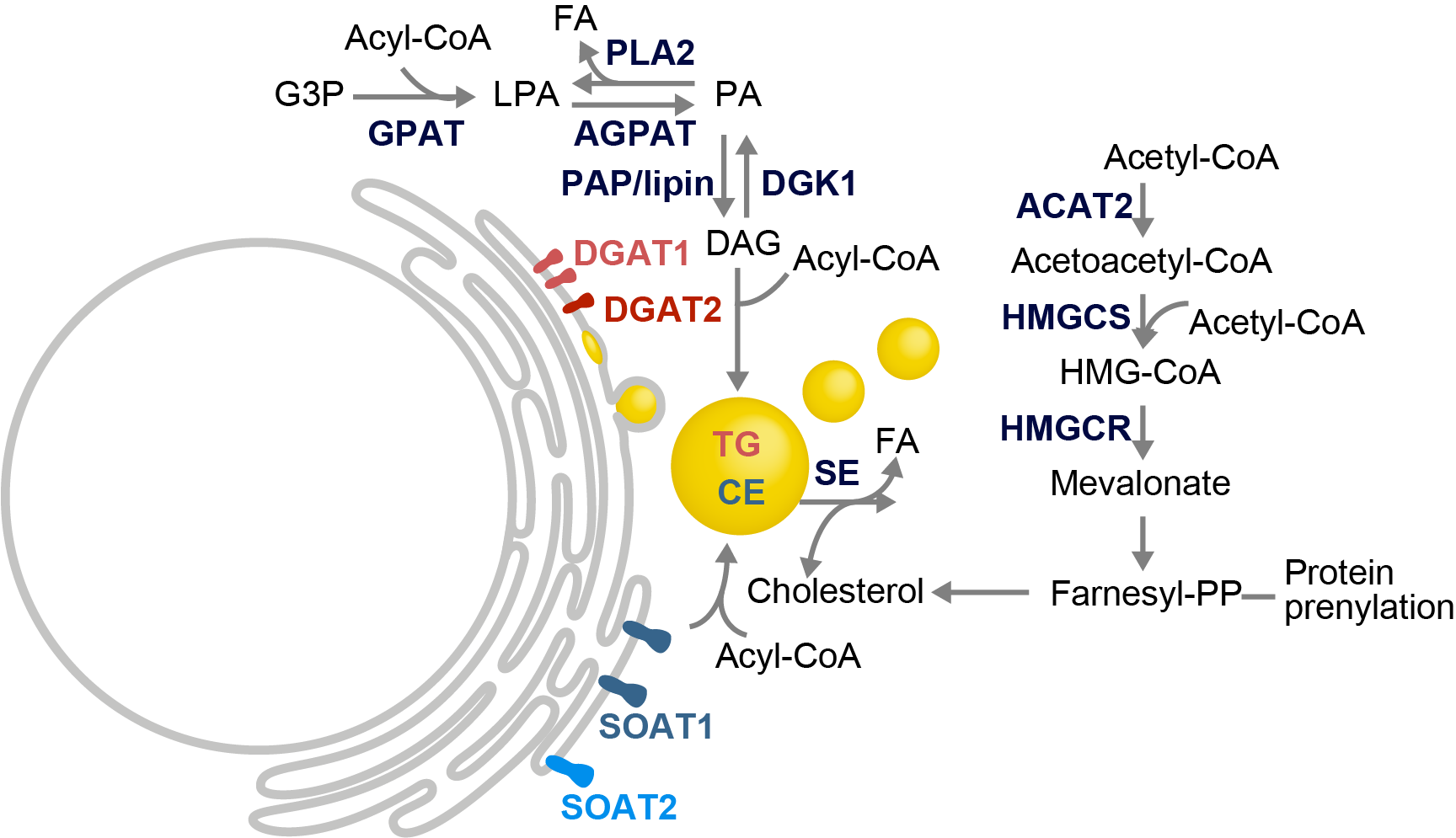

Metabolic remodeling of the host cell is essential for successful viral replication. For example, positive-sense RNA viruses induce membrane rearrangements in the cytoplasm as replication centers. These vesicular structures are thought to both protect the viral RNA from recognition by the host’s antiviral defense and to concentrate factors and/or metabolites required for RNA replication. The membrane rearrangements differ between viruses and it is not yet clear which lipid metabolic pathways are hijacked for their formation. LDs, known as the major storage organelles for neutral lipids in cells, are also hubs of metabolic processes. Pathogens, including viruses like HCV and DENV, exploit unique aspects of LD biology to support their own replication and persistence within the host. The goal of our research is to understand the interplay between viruses and their host to identify novel strategies for therapeutic intervention. The main projects are:

LDs and LD subsets in virus replication

Lipid metabolic remodeling in virus infection

Antiviral targets in lipid metabolic pathways

Cell biology of virus infection

LDs and LD subsets in virus replication (HCV)

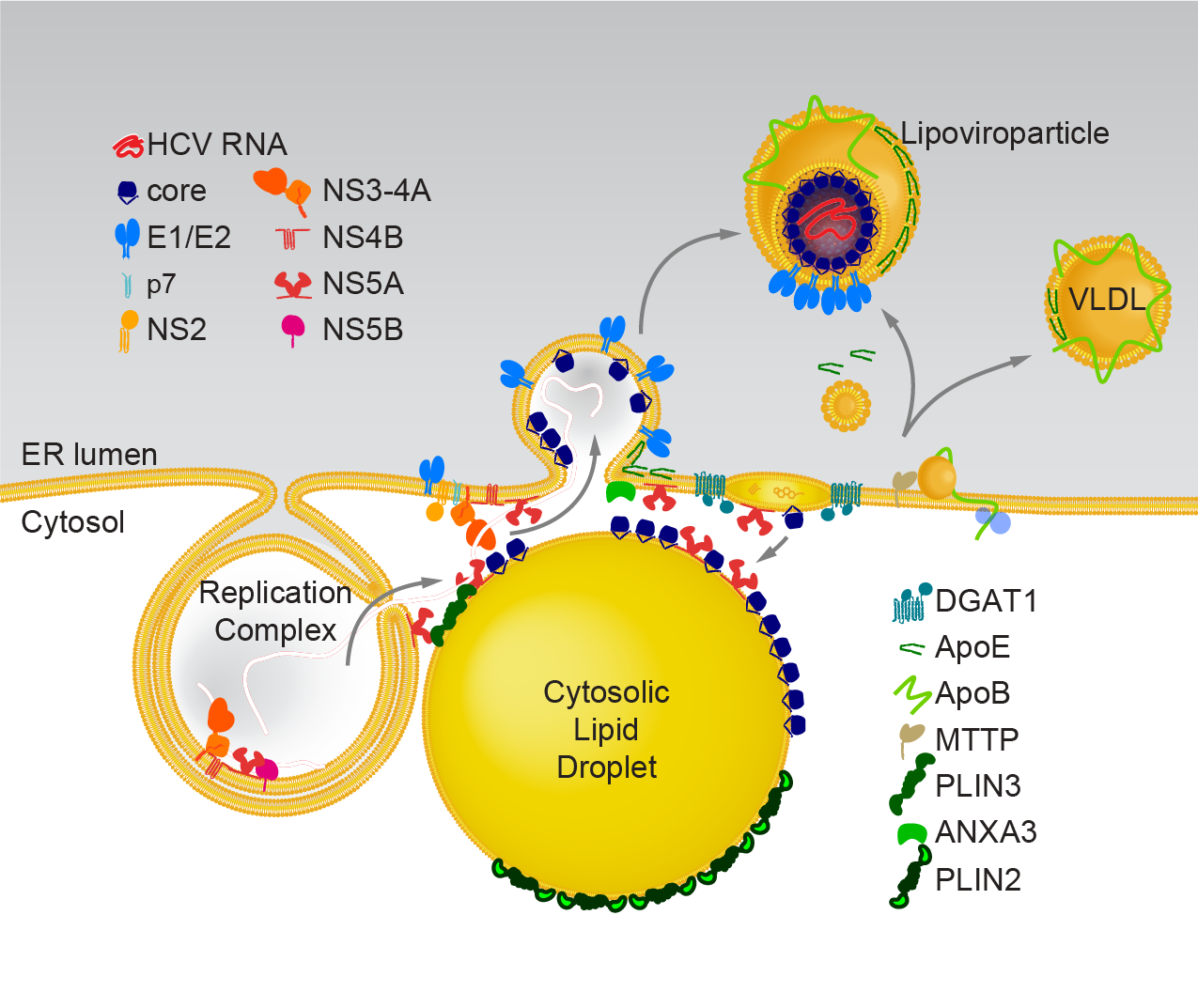

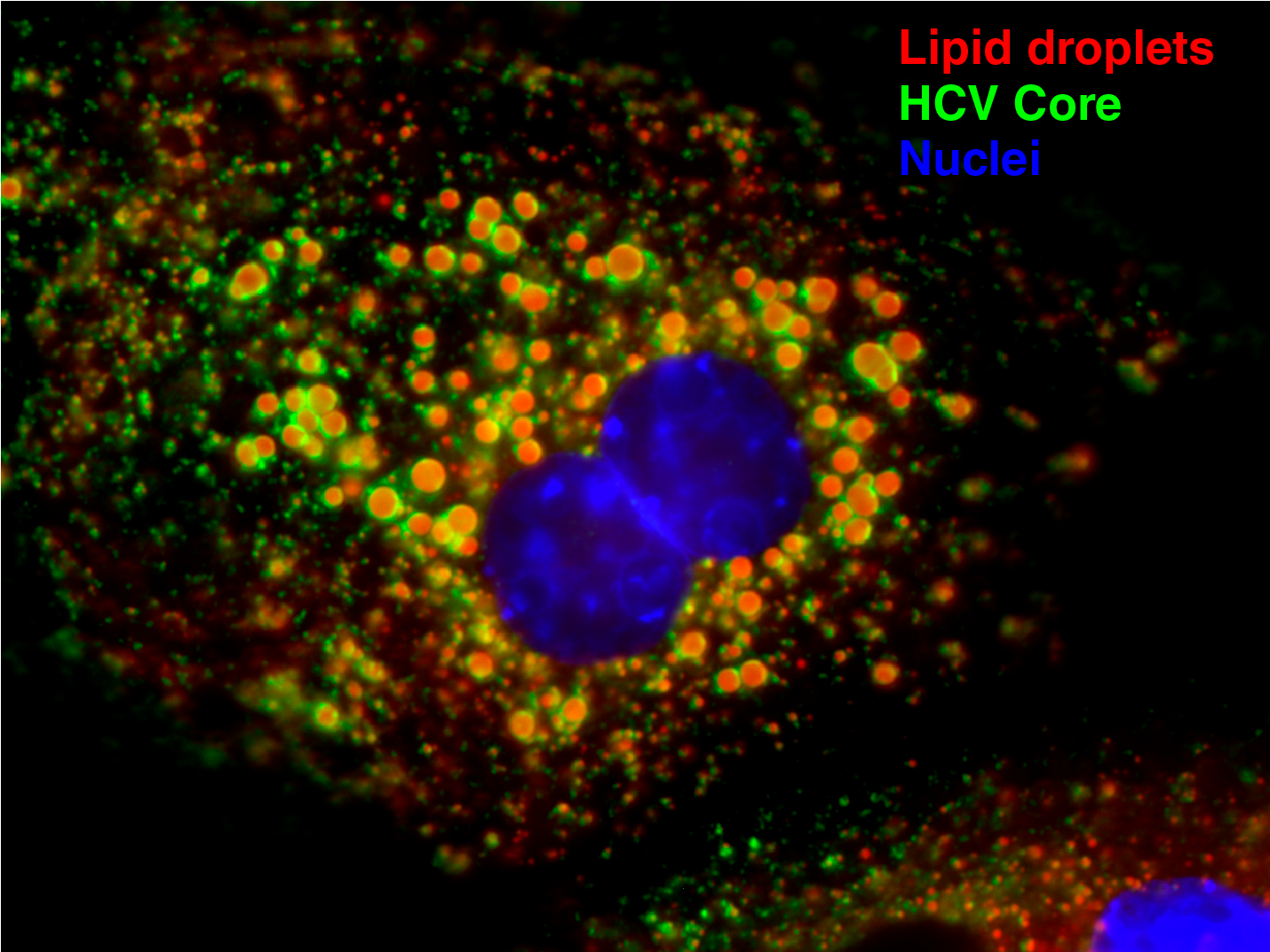

Model of HCV replication and morphogenesis at lipid droplets (Modified from Herker and Ott, J. Biol. Chem., 2012). HCV core localizes to lipid droplets in primary hepatocytes.

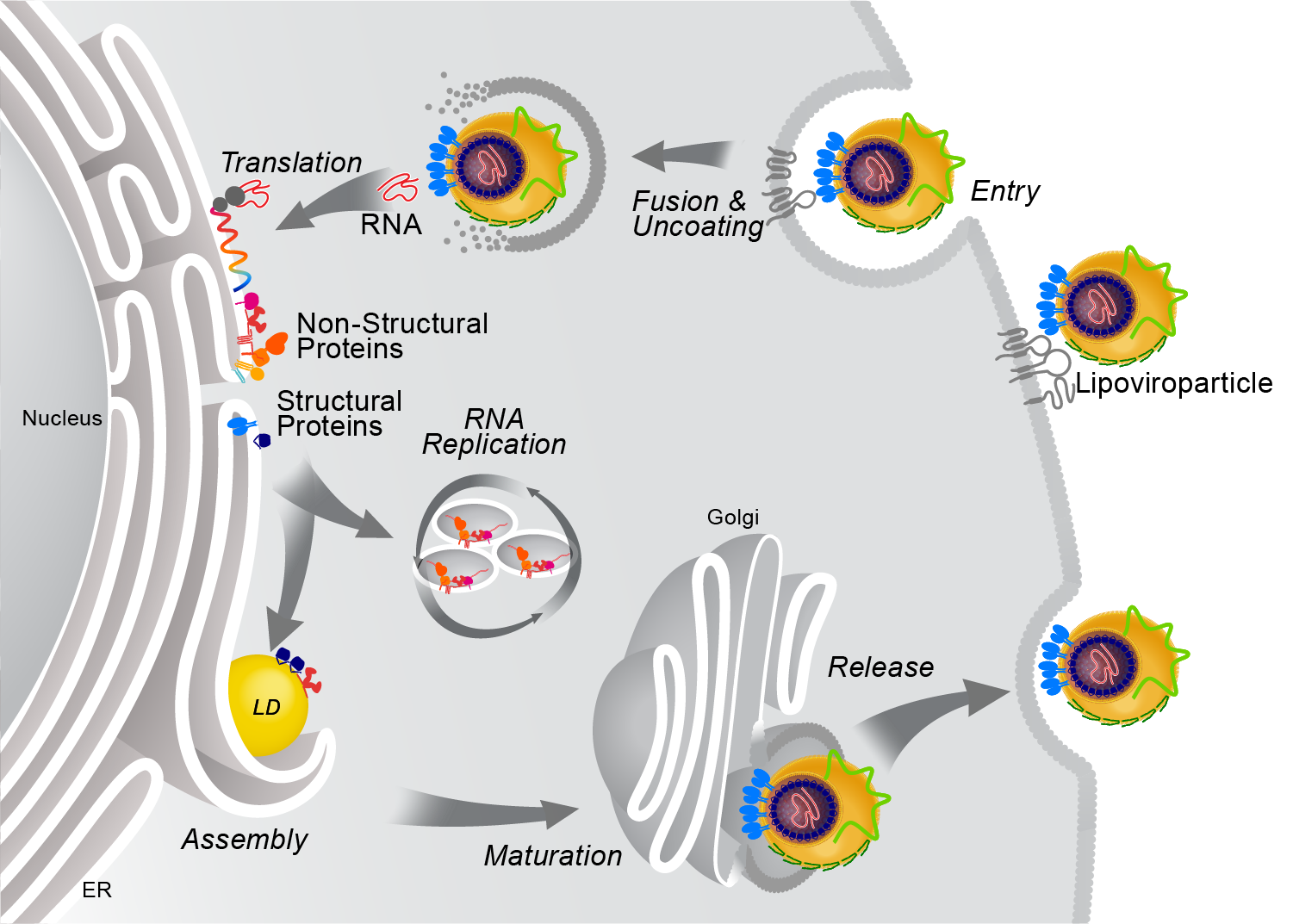

HCV’s enveloped infectious lipoviroparticles contain a single (+) stranded RNA genome and are tightly associated with lipoproteins and neutral lipids. The virus replicates in the cytoplasm of human hepatocytes and encodes for one polyprotein that is cleaved into 10 proteins, the three structural proteins (the nucleocapsid core and two envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2), the viroporin p7, and six non-structural (NS) proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B). The viral RNA is replicated by RNA replication complexes within ER-derived membrane structures termed the membranous web, which is detergent-resistant due to the presence of lipids that are associated with lipid microdomains, namely cholesterol and sphingolipids. Importantly, inhibition of cholesterol and sphingomyelin biosynthesis suppresses viral RNA replication in cells. We recently determined the lipid composition of HCV-infected cells and subcellular organelles and could link fatty acid elongation and desaturation to efficient viral replication (Hofmann et al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2018). Most likely, specific membrane fluidity and curvature is required for the formation of the RNA replication vesicles. This membranous structure is thought to shield replication centers from detection by pattern recognition receptors and contains single-, double-, and multi-membrane vesicles as well as cytosolic LDs that are the putative site of viral assembly (Herker and Ott, Trends Endocrinol. Metab., 2011, Herker and Ott, J. Biol. Chem., 2012). Our finding that functional LD biogenesis is required for efficient viral progeny production highlighted the importance of these host organelles for HCV replication (Herker et al., Nat. Med., 2010). Mechanistically, translocation of both core and NS5A to LDs requires triglyceride biosynthesis as inhibitors of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-1 (DGAT1) impair trafficking to LDs and subsequent HCV assembly (Herker et al., Nat. Med., 2010, Camus et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2013). HCV core protein also reduces LD turnover at the surface of LDs, thereby inducing steatosis in cultured cells and in murine livers (Harris et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2011, Camus et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2014). In our quantitative LD proteome analysis we observed that HCV disconnects LDs from their normal metabolic function and regulation and identified ANXA3 as a novel host factor for HCV maturation (Rosch et al., Cell Rep, 2016). Perilipin-2 (PLIN2/ADRP) is the major coat protein of LDs in hepatocytes. We recently investigated the consequences of PLIN2 deficiency on LDs as well as on HCV infection and found that PLIN2-deficient cells harbor lipid droplets trapped in double membrane sacs that do not support infectious HCV particle production (Lassen et al., J. Cell Sci., 2019).

LDs and LD subsets in virus replication (Flavis)

Within the DFG-funded Research Unit (Forschungsgruppe) FOR5815, we focus on investigating the function of lipid droplet subsets in flavivirus infection.

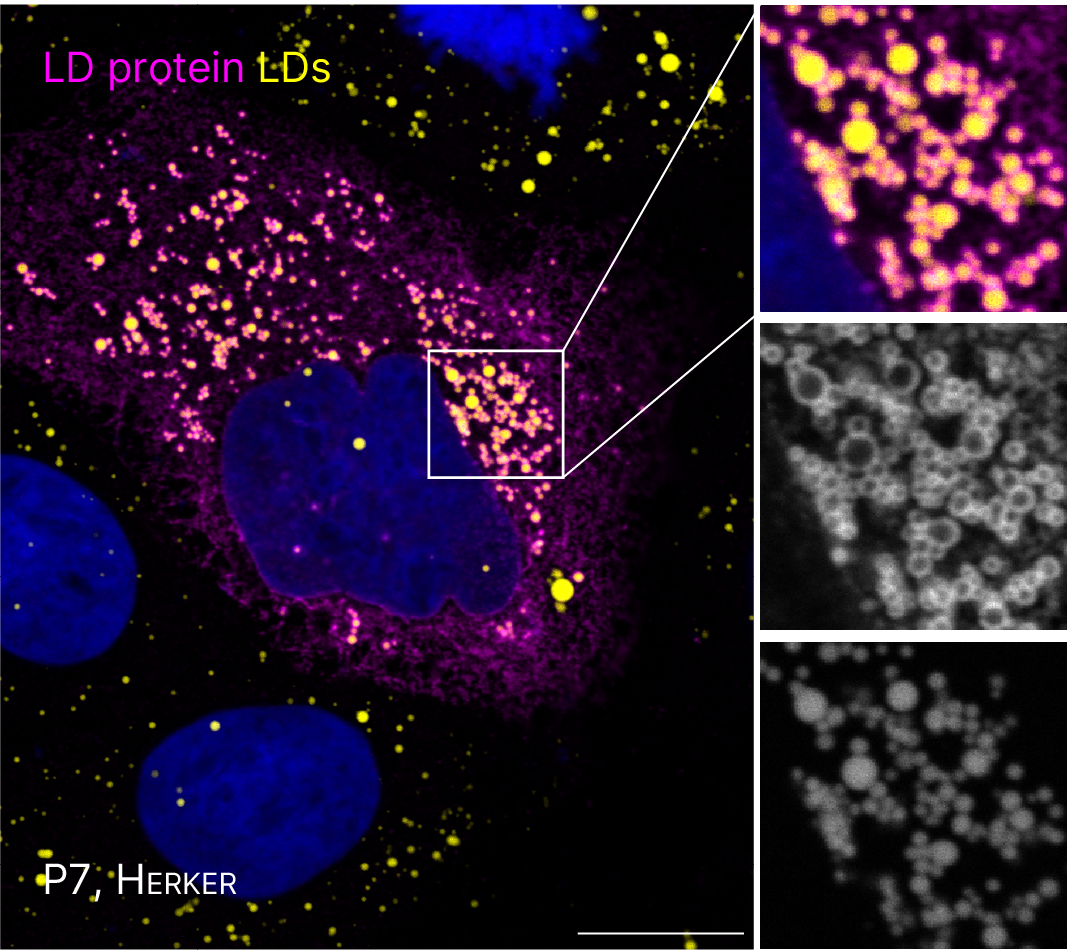

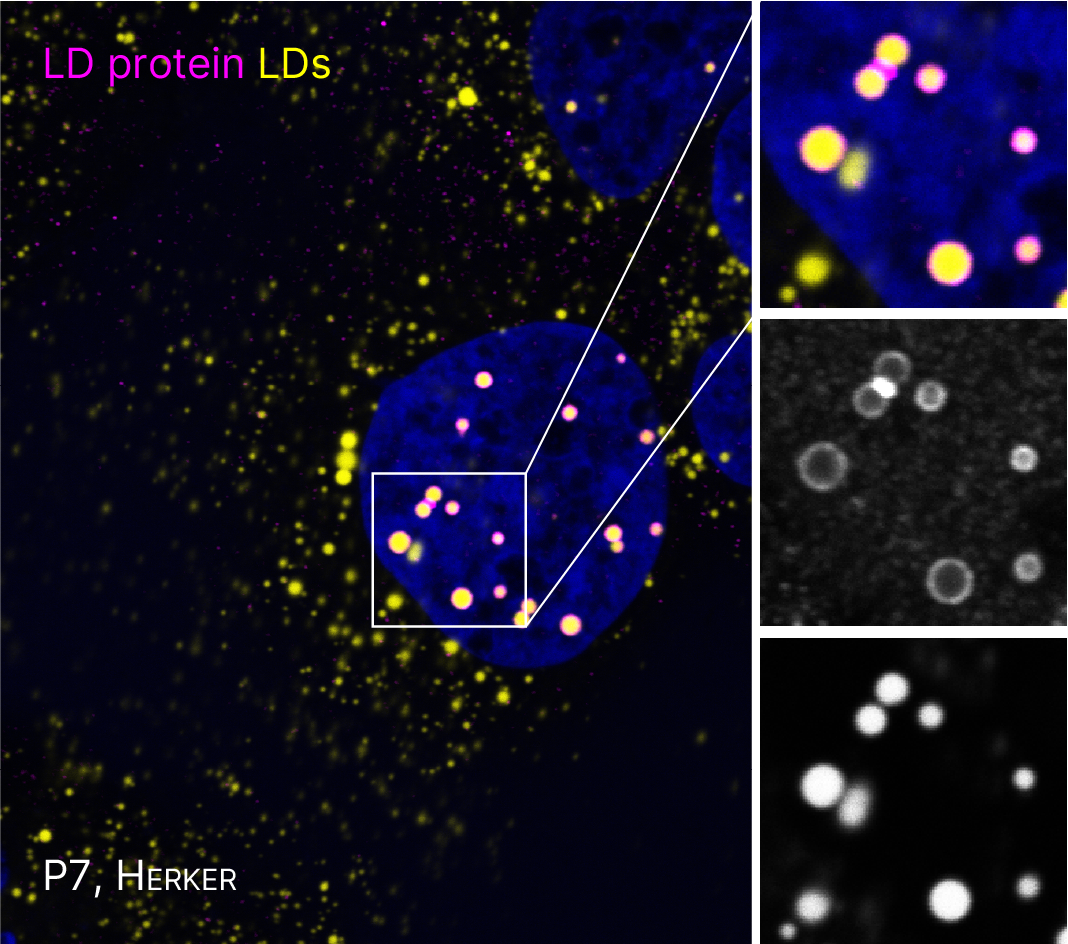

FOR5815 Project P7. Immunofluorescence microscopy of cells expressing viral proteins (mangenta) that localize to spatially distinct LDs (yellow).

Several flaviviruses depend on host LDs for replication (Herker, FEBS letters, 2024). In preliminary experiments, we observed that capsid proteins from different flaviviruses localize to spatially distinct LDs. Our goal is to assess how targeting specific LD subsets facilitates efficient viral replication. We will elucidate the molecular mechanism, timing, and functional relevance of the interaction of orthoflavivirus proteins with LD subsets. Further, we plan to investigate the consequence of specifically targeting LD subsets for lipid mobilization, a process required for generating membranous viral replication organelles (ROs) and for envelope formation of infectious viral particles, as well as for metabolizing lipids as an energy source for virus multiplication.

Lipid metabolic remodeling in virus infection

Pathogens hijack lipid metabolic pathways for replication and/or persistent infection. We hypothesize that positive-sense RNA viruses require similar lipid metabolic pathways for replication. We recently investigated in-depth the HCV-induced changes in the lipid composition and performed quantitative shotgun lipidomic studies of whole cell extracts and subcellular compartments (Hofmann et al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2018). Our results indicate that HCV infection reduces the ratio of neutral to membrane lipids. While the amount of neutral lipids was unchanged, membrane lipids, especially cholesterol and phospholipids, accumulated in the microsomal fraction in HCV-infected cells. In addition, HCV-infected cells had a higher abundance of phospholipids and triglycerides with longer fatty acyl chains and depletion of fatty acid elongases impaired HCV replication. Likewise, we detected an accumulation of oleic acid-containing lipid species and found that inhibition of the responsible desaturase suppressed HCV replication. These results suggest that elongases and desaturases are host factors required for HCV efficient replication.

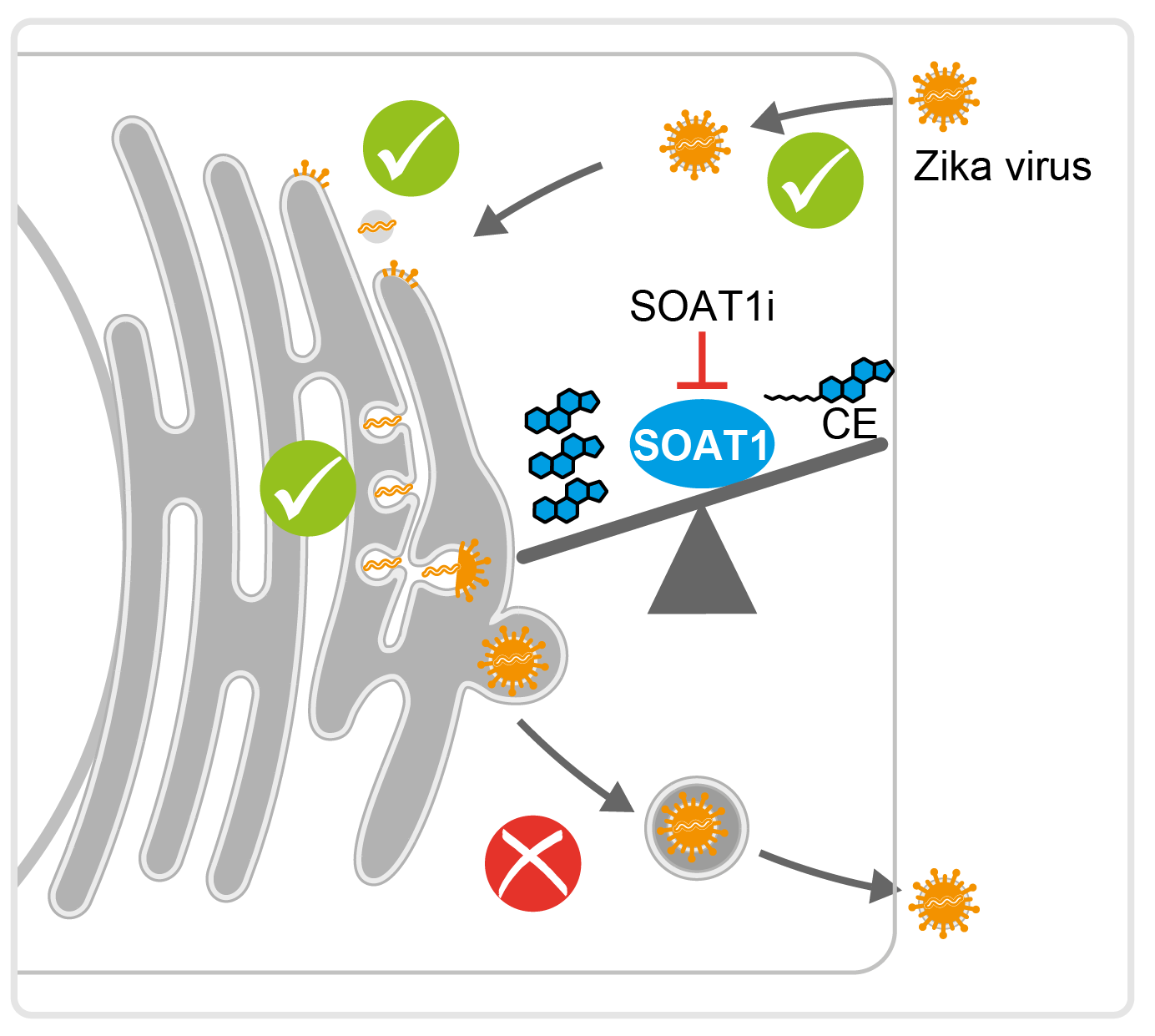

In our recent study, we used shotgun lipidomics to analyze cells infected by neurotropic Zika, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis viruses, as well as dengue and yellow fever viruses (Hehner, Schneider et al., Nat Comm, 2024. Early during infection, certain lipids accumulate, such as neutral lipids in Zika infections and various lyso-phospholipids in all infections. Ceramide levels rise in response to infections that induce a cytopathic effect. Additionally, there are significant changes in fatty acid desaturation and glycerophospholipid metabolism. Notably, reducing enzymes involved in phosphatidylserine metabolism and phosphatidylinositol biosynthesis lowers orthoflavivirus titers and cytopathic effects, while blocking fatty acid monounsaturation protects against virus-induced cell death. Interestingly, targeting ceramide synthesis has different effects on virus replication and cell damage depending on the enzyme affected. Therefore, lipid remodeling by orthoflaviviruses involves distinct alterations as well as shared patterns across viruses that facilitate effective infection and replication.

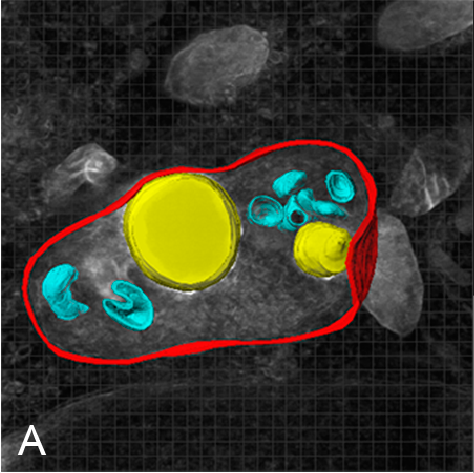

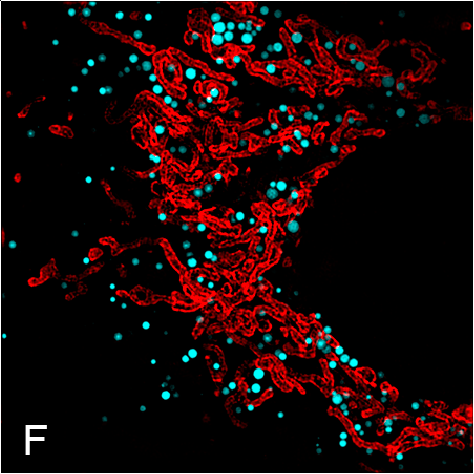

Cell biology of virus infection

We recently established workflows and microscopic methods to study and analyze virus-infected cells, LDs and associated proteins or cellular structures using confocal, super-resolution, and correlative light and electron microscopy. Examples are the use of super resolution microscopy to investigate the subcellular distribution of viral proteins in relation to LDs and correlative light and electron microscopy (Lassen et al., J. Cell Sci., 2019, Eggert et al., PLoS One, 2014, Vartiainen et al., J Synchrotron Radiat, 2014).

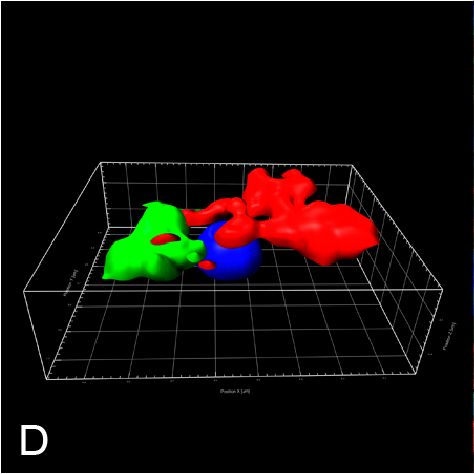

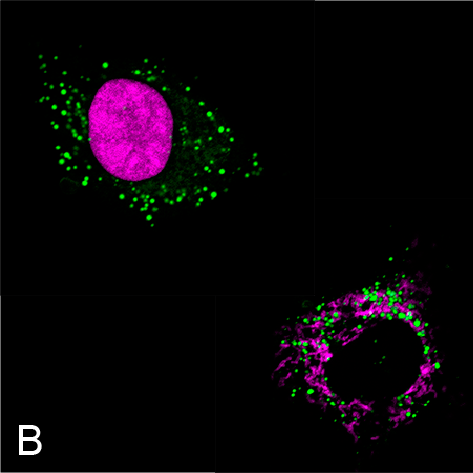

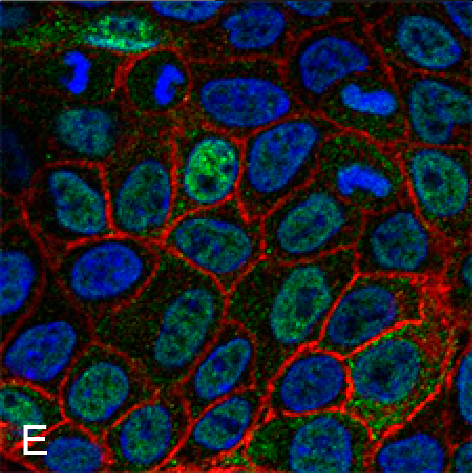

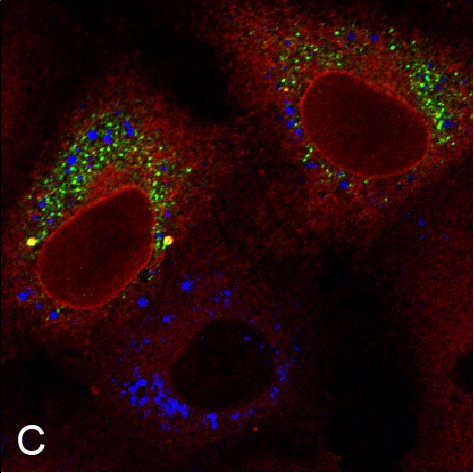

Examples of visualizing infection. (A) Electron tomography of HCV-infected PLIN2-deficient cells with lipid droplets (yellow), double membrane sacs (red), and HCV-induced vesicular structures (cyan) (Lassen et al., J. Cell Sci., 2019). (B) Lipid droplets (green) in HCV-infected (nuclear magenta) or uninfected (mitochondrial magenta) cells (Hofmann et al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2018). (C, D) Confocal and super-resolution microscopy of HCV-infected cells, HCV core (green), E2 (red), and lipid droplets (blue) (Eggert et al., PLoS One, 2014). (E) Occludin (red) and HNF4 alpha (green) expression in differentiated hepatocyte-like cells (Schobel et al., Sci. Rep., 2018). (F) Lipid droplets (cyan) and mitochondria (red) imaged using structure-illumination microscopy.